|

pby Tim Foster

Having just published the fourth instalment in a series of papers examining rural supply sustainability on the south coast of Kenya, it is timely to reflect upon some of the common threads that emerge from these related but discrete studies. Throughout our investigations we have examined rural water sustainability – and the determinants thereof – from all sorts of angles, including repair time, household financial contributions, revenue collection longevity, water source preferences, and – most recently – operational lifespan. The research has focused on Kwale County, which has provided a unique setting for understanding the drivers and dynamics of rural water supply sustainability. The region played host to the first large scale deployment of the Afridev handpump, a now ubiquitous technology in many African and Asian countries. The handpump installation programme, which ran for 12 years between 1983 and 1995, has since been held up as a ‘gold standard’ of rural water programming. As a result, a number of relatively rare data sources were available, including a consolidated set of installation records, water committee financial records dating back to the 1980’s, and a glimpse into the divergent operational outcomes over the course of three decades. Another consequence of the long-running handpump installation programme is that the institutional starting point for operation and maintenance appears to have been relatively consistent. This has allowed for a distillation of how environmental and geographic factors impinge upon operational outcomes. And despite the relatively small area in which more than 500 handpumps in Kwale are situated, our results have consistently showed groundwater characteristics and settlement patterns play an important role in shaping the long term prospects of community water supplies. Starting with the most recent analysis of handpump lifespans, we found the likelihood of premature failure was higher for water points that supplied water with elevated electrical conductivity (a measure of salinity), pumped water from greater depths, and were underlain by unconsolidated sands. The association with salinity probably reflects a user satisfaction issue – the propensity to pay for ongoing maintenance of a handpump is likely to be diminished when the water tastes salty. This is supported by our earlier findings that palatability was a significant determinant of whether or not a household would pay their monthly fees as well as their decisions about which water source to use. By contrast, the relationships with depth and geology signify differences in the maintenance requirements and the associated financial burden of keeping the handpump in working condition. Location of the water point also matters. The closer a community was to spare part suppliers, the lower the risk of failure. This could be directly linked to the transaction costs of obtaining spares – or simply be due to other socio-economic confounders. In earlier studies, the proximity of a water point to user households was also found to be a key driver of household contribution rates and water source choices. These findings show us that there are a variety of environmental and geographic challenges to keeping water supply systems working, and communities are each dealt a different hand. Some factors – such as salinity – may undermine the willingness of users to their sustain system; others – such as groundwater depth or distance to spare parts – may make it more difficult or expensive to do so. It is thus little wonder that rural water supply outcomes are mixed, even if the quality of implementation is high. How then can service delivery models level the playing field? Clearly, little can be done to change hydrogeological or demographic characteristics. However, their impact could be mitigated. One option is for a centralised approach to maintenance and repairs, whereby a tariff structure allows communities with troublesome hydrogeology to pay the same amount for a maintenance service as those communities enjoying more benign conditions (all else being equal). Such a scheme has been running for more than two decades in Turkana, a region in Northern Kenya that presents extremely challenging conditions for rural water supply operation and maintenance. Other variations on this theme are currently being trialled in Kitui County and in Kwale itself. While we await the results from these initiatives, early evidence suggests they can address the issues relating to more difficult operating conditions, but overcoming inherent differences in willingness to pay is more problematic. Ultimately, the case of Kwale shows that under favourable conditions, handpump supplies can last more than 25 years. The trick then is how to achieve similar longevity for communities that encounter more troublesome operating environments. Solving this conundrum will be essential if the global target of safe water for all is to be met.

1 Comment

OxWater research into the development of aquifer monitoring technology in rural Africa has been published in the journal Environmental Modelling & Software, and featured on the BBC Science & Environment.

The research uses machine learning methods to analyse data from low-cost sensors fitted to handpumps in Kenya. Vibrations in the pump handle can be analysed to indicate the water level in the underground aquifer beneath the pump. Africa’s shallow aquifers supply water for around 200 million rural Africans lifted by one million handpumps. Making use of the innovation reported in this research, rural handpumps could be transformed into a distributed monitoring network, providing vital information on groundwater availability. This in turn could enable action to protect water supplies and improve management of a resource that is under increasing pressure. This research is part of the Gro for GooD project, an UPGro consortium project funded by the UK Department for International Development, the Economic and Social Research Council, and the Natural Environment Research Council. On 17th September, the mystery surrounding the Samrat handpump which has been installed in the carpark of Oxford University's School of Geography and the Environment was revealed. Learn more about the pump's research purpose at www.oxwater.uk/oxford-smart-handpump.html or download the presentation below.

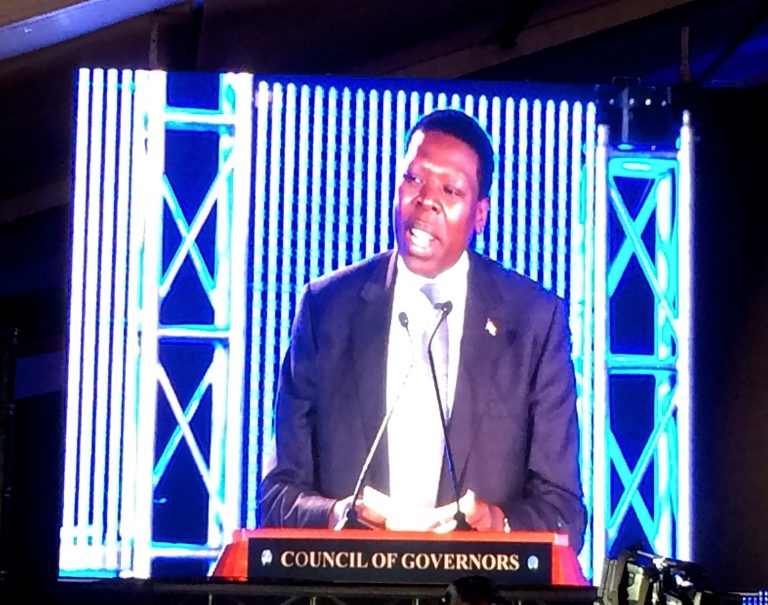

Cabinet secretary for Water and Irrigation, Eugene Wamalwa, closes the Devolution Conference on behalf of Deputy President of Kenya, H.E. Ruto Cabinet secretary for Water and Irrigation, Eugene Wamalwa, closes the Devolution Conference on behalf of Deputy President of Kenya, H.E. Ruto Re-posted with permission from: http://reachwater.org.uk/how-far-has-devolution-come-in-kenya/ How far has devolution come in Kenya? The Third Annual Devolution Conference In Meru, Kenya, April 2016 by Johanna Koehler Devolution is here to last! This message was delivered loud and clear at the Third Annual Devolution Conference in Kenya, organised by the Council of Governors. In three years this conference has become an important gathering of national and county government representatives, academia, private sector and civil society to discuss the benefits and challenges of devolution. A brief I wrote on water policy choices of Kenya’s 47 county governments sparked interest among national and county governments and led to an invitation to share key findings at the conference to an audience of over 6,000 people. A new political era for Kenya Devolution, also known as decentralisation, was set in motion back in 2010 with a new constitution that introduced two tiers of government, the national and county level, and devolved certain functions to the counties, including water and health services. The 2013 elections led to the establishment of 47 county governments with affiliated county water ministries – new institutions that have developed their water service delivery mandate throughout the three-year transition period. This year’s conference marked the end of the transition period in March 2016, when all functions outlined in the 2010 Constitution become fully devolved. It is also a critical time politically as Kenya’s 2017 national and gubernatorial elections are approaching fast and competition over the Governors’ seats is rising. The delegates passed 18 resolutions to reinforce devolution and hand over all devolved functions to county governments. Some of the contested functions were the water, health and irrigation sectors Managing water services under devolution Water is one of the mandates divided between national and county governments; it remains a national resource, but water service delivery is now a county responsibility. As water crosses county boundaries, it is clear that national-level institutions are needed to navigate conflicts and regulate water service provision. However, counties are asking for more autonomy and there is a need to avoid duplication of efforts between the national and county institutions. The research I presented at the conference shows that the water service mandate is interpreted differently by Kenya’s 47 counties. Not all counties acknowledge their responsibility for the human right to water which entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water. This suggests a need for county water policies to be streamlined so that regional disparities don’t grow and transformative development is sustained. These findings come from a unique opportunity I had to survey all 47 county water ministries in Kenya at a summit organised by the Water Services Trust Fund to develop a prototype Country Water Bill. I found that while counties are making major investments in new infrastructure for water services (where the majority spend more than 75% of their water budgets), maintenance provision and institutional coordination are often neglected. This raises a concern about the sustainability of water services and could slow down progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goal for water. Optimistic but uncertain outcomes for the poor So will devolution lead to more accountable politics and better water services for the poor? This is one of the research questions that the REACH programme is asking in Kenya. A Water Security Observatory in Kitui County aims to understand how institutions can be designed to reduce rural water security risks, for example from rainfall variability, unreliable infrastructure and irregular financial flows. In the water sector and elsewhere, the Devolution Conference was marked by a strong momentum for change. County governments committed to tackling social inequalities through targeted allocations of funds to relevant sectors, and urged everyone to join the fight against corruption, which is seen as a key obstacle to devolution. The conference was certainly used as a political tool for building support for devolution. Delegates were told how school attendance has increased because of bursaries provided by Turkana County Government; in Machakos County, people walk shorter distances to get medical attention; Kisii town has a 24-hour economy after the installation of solar lighting; while Mombasa County has introduced a feeding programme for primary school pupils. And so the success stories go on. Overall, the conference provided an important platform to share progress made in Kenya’s devolution process with the key political actors, and also to flag new or existing challenges as county governments manifest their power. It is remarkable to see such a transformation in Kenya’s political system within the short timeframe of only three years. It seems the water sector will gain from these changes, but only the future will tell if the newly devolved system will benefit the poor. Read the Policy Brief – Water Policy Choices in Kenya’s 47 Counties OxWater's Rob Hope gave a keynote at the 10th Anniversary Conference of the ESRC-DFID Joint Fund for Poverty Alleviation Research Lessons from a Decade’s Research on Poverty: Innovation, Engagement and Impact, Pretoria, March 2016. View powerpoint: Translating Research Ideas into Water Security Impacts for the Poor in Rural Kenya

Patrick Thomson won the prize for the best poster at World Water Week 2015 for the work that he and colleagues at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at Oxford have been doing on shallow groundwater monitoring using Smart Handpumps in Kenya.

A briefing note based on the information presented in the poster can be downloaded: |

OxWaterOxWater is an interdisciplinary and international collaboration led by Oxford University to address the enduring problem of achieving sustainable water systems in Africa and Asia. Archives

March 2018

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed